2021/09/15

Time blocking

Recently, I’ve started doing time blocking, a practice where you set up dedicated blocks of time to certain tasks, and exclude all other distractions. It helps set your intentions and directs your focus to specific tasks and projects.

What is time blocking?

When you time block, at the start of your day you write a timeline, place tasks you want to tackle on that timeline and assign durations to them. In a sense, it’s a version of day planning with duration information.

Then, you start to work on the tasks in that timeline. You start the tasks at the time you specified, and work on them for the duration you blocked. If the events of the day knock you off your initial blocking, then you make a new timeline from where you diverged, and re-plan the remainder of the day.

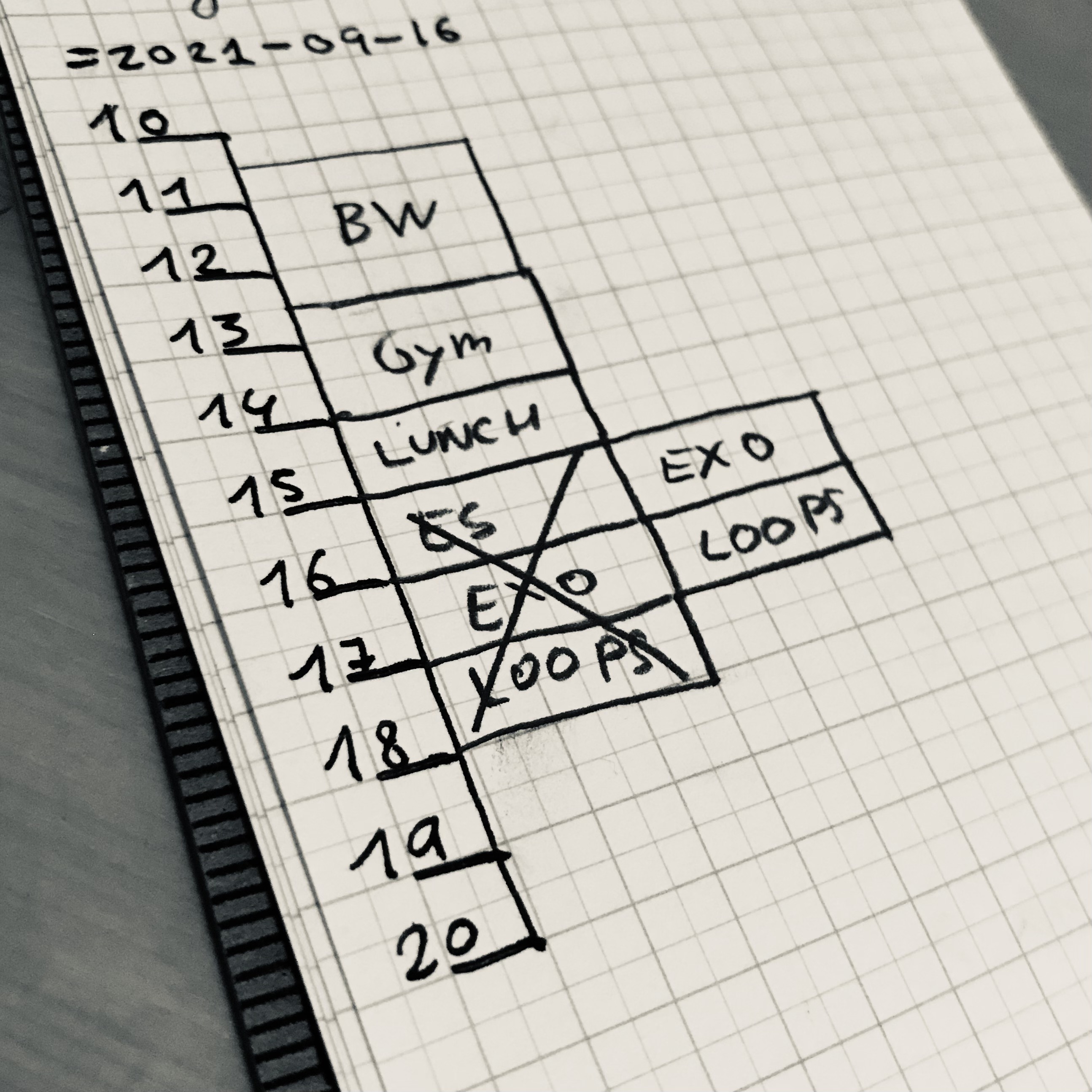

I typically do this in a paper notebook. Since it’s transient information that I don’t intend to save and that’s not useful for me. To get reports on where my time actually goes, I do time tracking instead.

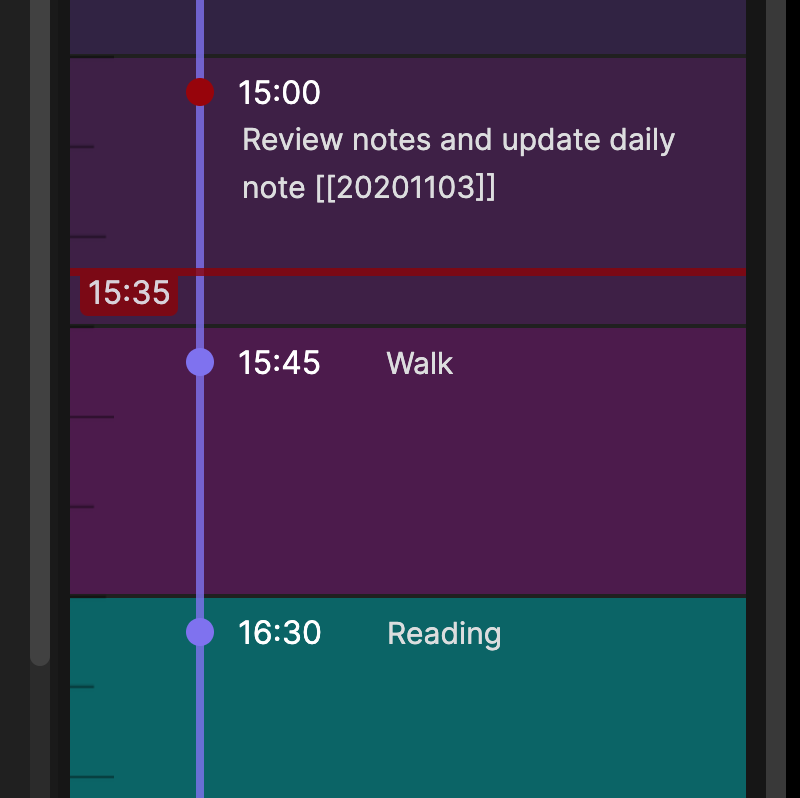

I’ve also tried with other tools, like the Day Planner plugin in Obsidian, but I found it too clunky to work with.

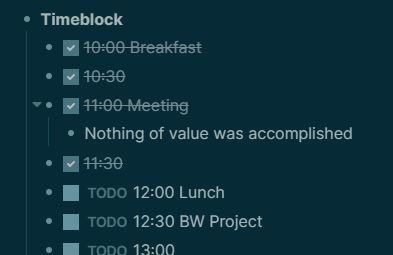

When a notebook is not an option, I have set up a template in Logseq with a list of times, set to a granularity of 30-minute chunks, which works for me and the kind of work I do. Then, I fill the points where a task or project starts with the task name

The advantage of this method is that it’s really easy to annotate tasks afterwards (like, for example, adding some notes for a meeting indented below the task entry for that meeting)

In this video, Cal Newport explains the process well. You don’t need to get the official planner. You can adapt any notebook. I find ones with grid pages help when drawing the blocks.

My observations

I admit I was reticent to try it at first. I’ve always hated strict schedules, favoring a more free-flowing organization of my day.

The idea didn’t seem like it had much merit beyond a timetable and would be a rehash of the rigid timetables of academic institutions. I was wrong. The crucial differences are:

- It’s a plan you make on your own terms, and you write it down at the start of your day (hence, it still remains pretty flexible)

- It’s not meant to be a static, accurate record of where your time goes or an anxiety-inducing deadline, just a guideline of where to spend your limited time each day (for a record of what you actually do, you would use time tracking)

After doing it for a few weeks, I have to say the benefits are evident. Before, I always felt the vague sense that there was no way I could get to everything I wanted to achieve, that wasn’t enough time in the day. With time blocking, now I have the certainty that there isn’t enough time!

Jokes aside, it has really helped, pushing me to do more stuff more regularly. Before, I was (sometimes) using the pomodoro technique, with a physical kitchen timer. The timer helped with intentionality and pushing myself to start the work even when unmotivated. Afterwards, it was easy to get the ball rolling.

However, the pomodoro technique was developed in the the 80s, a time before digital tools were ubiquitous in our lives. The 25/5 minute intervals feel pretty arbitrary, and evidence shows that they don’t fit a human scale of contemporary knowledge work anyway.

Notably, research conducted at Draugiem Group found out that their 10% most productive employees worked for 52 minutes and then took 17 minute breaks. While this reaffirms the idea that taking frequent breaks is positive for productivity, a lot of folks of course took the wrong lesson out of it and were quick to mint the “52:17 rule”, following a precise 52-min work interval with a 17-min break.

You should not do this. You should work on your task until you feel you need a break, and then take a short break before returning to work. Worrying about precise minutes of work will just add anxiety to your mind and affect your focus. Remember that these figures are just an average of the working habits of some people. Furthermore, just a fraction of the “most productive” employees of a single company. The results from this small sample size shouldn’t be taken as gospel, and more importantly, you shouldn’t confuse correlation with causation. Just because productive workers take a break after 52 min of work on average, doesn’t mean that working for 52 is a magic number that will make anyone who imitates it more productive.

Personally, my own timings float around between 50 and 110 minutes of focused work, followed by breaks of around 20 minutes, depending on what I’m doing during that break.

Another advantage of time blocking is that, as you block days and execute your tasks, you start building up an intuitive sense of how much time you need for each activity. If you see that you’re blocking 1 hour for the gym, but it always ends up taking you 1 hour and a half, that’s some knowledge you can use to adapt for future days. Like a built-in review for time estimates.

It lets you get a much better sense of how realistic your time planning is.

It also allows you to build a sense of what are the times of day when you have more willpower, are more motivated or are in general more productive, so that you can prioritize your most important project for the times when you can do your best deep work.

I strongly recommend trying it.